|

Written by Gretchen Vogelgesang Lester Last week at the gym, I brought up to someone that I used to be an aerobics instructor. I briefly recounted some stories about that experience and thought sadly of the phrase “used to be”. I truly no longer consider aerobics instructor as part of my leadership identity, partly because I haven’t taught a class in over 12 years, but even more so that it just doesn’t enter into my daily activities anymore. It’s simply not an identity I "wear" anymore.

When we teach about identities and sub-identities, we discuss how students should list their current sub-identities, and how they can become more or less salient over time. But I think it is also a good exercise to revisit past identities and think about how they shaped your current identities. Just like an old broken watch might offer a new life with its parts, our past identities can offer competencies that shape our new identities. I did not know, when I was an aerobics instructor, that I would eventually preside over a different type of classroom – but looking back, some of the things I needed for that identity are still with me. I work hard to project my voice to all my students in the room. I also look for understanding in their eyes, making sure my students are “with” me as I broach new topics. I was lucky as an aerobics instructor - I did not have to compete with the lure of social media (smart phones did not yet exist, and texting on a flip phone was excruciatingly painful). But, I did contend with side conversations, varying levels of ability and fitness, and jockeying for space and materials. I also had to continue to learn new techniques (yes, even aerobics instructors have continuing education requirements). I also had to manage feedback from paying customers. So, although the days of choosing music, creating routines, and leading a class through a challenging physical workout are over, I still put in to practice many of the competencies I acquired in the pursuit of excellence in that sub-identity. When I started to write up this blog entry, I thought the word “discard” was a little too harsh. As researchers, we do use this terminology – we adopt and discard identities as we change and adapt throughout our lives. But to say we discard identities makes it seems like we throw out everything about that identity. Unfortunately, the synonyms for discard are equally as negative: abandon, dispose of, ditch, dump, eliminate, jettison, reject, remove, scrap, shed, etc. So perhaps instead of saying we discard of our old identities, we should say instead that we have sub-identities that have evolved into something new and different. What previous identities had you at one time embraced but now have evolved into something new?

0 Comments

Why a Leader Identity Narrative Matters Written by Rachel Clapp-Smith Every semester, we ask our students to write a leadership narrative as their final project for the course. It’s a fairly involved process of multiple reflection points that we provide over the course of the semester so that by the end, they should have a fairly good sense about how they see themselves and how their leadership aligns with the multiple domains in which they lead.

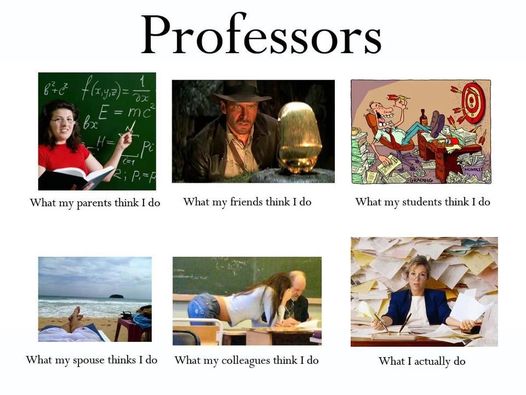

In my instructions, I ask the students to pull into the narrative “the good, the bad, and the ugly” of their leadership, because I want the narrative to be complete, as they are a leader, not only as they want to be. Of course, my use of the language comes from an article written by Mats Alvesson and Stefan Sveningsson, two professor at Lund University in Sweden. Their article is titled “Good Visions, Bad Micro-management, and Ugly Ambiguity,” and describes the contradiction in how leaders see themselves (good visions) versus how they actual describe their leadership behavior (Bad micro-management). In their research in a knowledge intensive firm, they found that managers described good leadership as being strategic and visionary and bad leadership as being micromanaging and directive. And yet, when asked to describe the behaviors they use to lead, the managers described behaviors that aligned with their descriptions of bad leadership. Finally, the ugly ambiguity represents the reality that our hopes of leadership in making a well-ordered environment, where it is clear what needs to be done, who needs to do it, and how leadership affects it, is simply not possible. Leadership, in reality, is messy. We try to get our students to face these realities – leadership is messy and building a leader identity is hard work, because it requires facing these uncomfortable realities that often we behave as bad leaders, despite what we believe about good leadership. We were asked recently to explain the proverbial “so what?” about our research (a question that academics like to ask each other). It’s nice to have a leadership story about yourself, but so what? Why does it matter? Well, if it is an honest story, that acknowledges the good, bad, and the ugly, then it helps students know where they need to focus their development as a leader. If I think good leadership is about listening, but in my practice I cut people off or don’t really hear what they are trying to say, then I am not acting like the leader I think I should be, and I have a lot of work to do. But I also then know what I need to work on. And that is why a leader identity narrative matters. It helps us see the path to becoming the leader that will be successful in the many contexts where we lead. Written by Michelle Hammond Memes that illustrate what various people think have been popping up all over the place for just about every occupation under the sun. Why have they become so popular? They are fun. They make us laugh. But they also reveal some truth. They present an opportunity to take a light-hearted approach to a few things that are rather deep.

1) Big differences can harm relationships. We might laugh that our spouse thinks we’re lounging on the beach when we’re really buried in a pile of papers, but those misconceptions, when left to fester can create real rifts in our relationships. While it might not be possible for everyone to have a complete understanding of what everyone else is doing, working towards clarification with those who matter most can be extremely useful. What your boss thinks you do matters. What your co-workers think you do matters. What your family thinks you do matters. Take some time to see yourselves through the eyes of others. 360-degree feedback is a great way to do this – in work, in the community, and at home. And most importantly use that information to spark meaningful discussions about expectations, commitments, and opportunities to learn and grow. 2) They create a shared sense of identity for those who share that occupation. Knowing that I have a shared experience of being misunderstood a “college professor with the summers off” strengthens my tie with other college professors as we examine our jam-packed summer to do list. 3) They highlight that our identities are both personally and socially influenced. For many, the link between what others think we do, and who others think we are is tight. Our own sense of identity - who we are, what we do, and our value - is in part, determined by what other people think of us. Of course, the degree to which others influences our sense of self varies from person to person and across our life stages, but undeniably, our identity is both personally and socially influenced. We need to work towards a more accurate understanding of how others view what we do and how we come across as well a solid sense of who we are that doesn’t fluctuate based on others’ changing perceptions. What do others think you do? Last week, I had the pleasure of seeing the Broadway tour of Finding Neverland. This show is an adaptation of the 2004 movie of the same name; the story of J.M. Barrie, the creator of Peter Pan. As the story goes, J. M. Barrie was inspired by the young children he saw playing in the park one day, and created a world where boys never grow up, fight with pirates, and live with fairies. At one point in the play, J. M. Barrie and the cast participate in a number called “Play” to shake the serious actors out of their cynical take on the child’s tale. It begins with this phrase:

“Can you remember back when you were young, when all the simple things you did were so much fun? You got lost somewhere along the way, you’ve forgotten how to play, every single day.” In our leadership development exercises, we ask our participants to create their leadership timeline from their very first memories to 20-30 years into the future. The past timeline highlights moments that stand out as formative; the future timeline is intended to create purposeful opportunities for leadership development. Some participants focus on their experiences; others note movies, books, tv shows, etc. that shifted a view of their thinking about leadership. But what about the moments that aren’t as memorable? What about those times just playing? Pretending to be a magician, a ship’s captain, a lion tamer…or just creating games with friends to fill up time in the day? Identities slipped on and discarded as quickly as the imagination could come up with the next idea. Just simple fun. I hope everyone has those types of fun memories. But as we grow older, we seem to forget how to play. Yes, we have more responsibility as adults, experiences have taught us self-preservation and society shapes our thoughts on what is foolish and what is logical. But perhaps we have lost too much? Perhaps not everything needs to be so serious. Perhaps we can still find opportunities for playfulness. In my opinion, one of the best attributes of multi-domain leadership is the freedom try out different leadership styles in domains other than work. In the same way children are free to try on different identities while at play; participation in other domains allows adults to also try on different leadership identities. Are there simple things you did when you were young that you can re-incorporate into your life? Can you volunteer in ways that allow you to play? Are there things you can observe that make you happy but also connect to your leadership abilities and challenges? For me, watching musical theater is a delight. And Finding Neverland reminded me that we shouldn’t forget to play (and to give thanks for the professionals who can entrance us with stage magic!). What have you experienced lately that allows you to learn from areas outside of your work? Written by Rachel Clapp-Smith Image by Polly Clapp My grandmother passed away yesterday. As many families do at the time of loss, my family got together to remember, start the process of grieving, and reflect on the mark my grandmother made on the world. Whether we are intentional or not of making a mark on the world, we invariably do. There are so many wonderful qualities about my grandmother – she was kind, brave, self-determined, strong willed, and always friendly. She never wanted to be a bother to others and she didn’t let adversity slow her down. In fact, the day before she died, she stopped breathing for a little bit. But then she started breathing again, came back to, and went to lunch. That was simply the type of women she was, not be let a moment of death slow her down her keep her from lunch.

When I first started to study leadership formally, that is, in business school, and I was asked to think of a leader who inspired me, Grandma always came to mind. I never knew if it was cliché to think of my grandmother as an influential leader or, worse, sometimes I didn’t really understand why I felt influenced by her. But I did always see her as someone whose behavior I wanted to model. You see, she always had the respect of others because she always respected others. She never demanded trust or respect, but always earned it through integrity and relatedness to humanity. As much as I want to tell you more about what an amazing women she was, the true point of this blog post is to reflect on our futures and our ends. Many leadership consultants will take clients through an epitaph exercise, in which they project on how they would like to be remembered. As kitschy as this may seem, in moments of loss, you can’t help but be moved by the legacy some people leave behind, how fondly they are remembered. It is years of consistent behavior that build these legacies and most often, they are projected onto many domains, not just work. I raise this domain orientation, because at mid-life where I sit at the moment, I seem to be thinking much more about how I can have an impact at work, but at life’s end, will that really matter? Will I be comfortable hearing people I worked with fondly remembering what I did for the organization at the expense of my kids and grandkids reflecting on how little they knew me, how successful I was at work, how much stress I brought home, and the family sacrifices I made for my career success? No, that doesn’t appeal to me. So, when I think about my leadership and the mark I will make on the world, in which domains is my mark the most important to me? By seeing how my many domains are integrated, it becomes easier for me to see how what I value in my work domain can enrich what I value in my family and community domains. What do you want your legacy to be? How will your domains remember you? .Yesterday, Villanova beat the University of Michigan in the NCAA Final Four championship game. Scanning through media attention of the game, the focus appears to be on two key people largely made responsible for that win: Villanova’s head coach, Jay Wright, and star player, Donte DiVincenzo.

Coach Wright led Villanova’s second championship win in three years. He even looks like a celebrated hero in his tailored suits and Clooney-like countenance. DiVincenzo has been described as “The Michael Jordan of Delaware” and was nominated the Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four. How much of Villanova’s win was down to this coach and star player duo? A good deal, according to what I’ve seen in the news. However, the abilities and dynamics of the other team members, the assistant coaches, the resources invested, and even the fans themselves also contributed to the win. Perhaps Michigan didn’t step up as much as they could have, giving Villanova that much more of an edge. However, we’re less likely to see these contextual factors mentioned in reports of the win. Why? We can get caught up in a romantic idealized view of leadership. We want a hero. We want someone to be responsible. We love a good hero or villain story! Perhaps this year’s scandals in the NCAA built up our need for a hero—a beacon of light in dark basketball times. However, we see this all the time in the media, in our workplaces, communities, families, and even in ourselves. The question becomes: “How much does leadership matter?” How much do CEOs, presidents, coaches, and leaders influence outcomes in sports, communities, and businesses? It can be difficult to pin down an exact answer to that question, but it’s clear there are dangers in giving more to their contribution than what’s due. The romance of leadership represents a bias in explaining outcomes in which we over-attribute outcomes to leaders and their leadership. Leaders take credit for success and we grant that to them. We blame them for failures that may or may not be within their control. We want someone to be responsible. However, there are a few dangers in holding a highly romanticized view of leadership:

At the end of the day, does leadership matter? Do we need strong leaders? Absolutely! Not just for what they do themselves, but also for their influence in recruiting good people and bringing out the best in them, and for shaping an environment in which everyone can thrive. But these points should be moderated by an awareness of the dangers of a highly romanticized and heroic view of leadership. “Lead..Follow..or get out of the way” (George S. Patton) Often when we discuss leadership, we think of it (as Dr. Palanski recently noted ) as one person telling others what to do. He discussed the idea of shared leadership, where the group decides together to take action. Beyond the idea of shared leadership is also the role that followers play in the leadership process. In a true leadership process, the followers are equally as important as the leaders.

A leader cannot lead without followers choosing to engage in the process. One way of looking at this is to think about different behaviors that we enact when interacting with others. Do we “claim” a leader role by speaking first, sitting at the head of the table, or volunteering to seek out a solution to a problem? Do we “claim” a follower role by offering to help when needed, or holding back in the moment because we have other responsibilities? Do we “grant” someone else the leader role by offering to help when needed? Do we “grant” someone a follower role by delegating a task for them? What about those who avoid taking a position at all? Think back over your behaviors at work, at home, and in your community. What roles do you take in each of those domains? We’ve discussed quite a few ways to develop your leadership abilities over the past year, but let’s focus on followership for a second. Most of us must take follower roles in some areas of our lives; we are all too busy and only have a finite amount of resources to continually be in the leader position. So when we do claim a follower role, are we acting in good faith? Are we supporting our leaders to the best of our abilities? Research on followership notes individuals may take different perspectives on the meaning of the follower role. In one view, a follower is anyone who formally or informally reports to an individual in a leadership role. The other approach, similar to what I discussed earlier, is the idea that the follower has an active and important role in the leadership process. This view moves beyond the idea of followers as sheep who blindly follow their shepherd to one where followers have an active duty to participate in the goals set out by the organization, family, team, etc. Proactive followership behaviors can include feedback-seeking, using influence tactics, taking initiative, and in some cases, breaking the rules when necessary. Opportunities for proactive followership do depend on the types of leaders present. Some leaders feel threatened by proactive followers and would prefer a group of subordinates (word choice here is deliberate) that do not question the leaders’ actions. However, more effective leaders look to their followers to help accelerate the organization/team/community towards its goals. The latest research on followership shows numerous positive outcomes from proactive followers. If you find that you are looking to be more proactive – at work, at home, in your community - the first step is to think about the behaviors you exhibit. Are you actively granting leadership opportunities to someone else, which is part of an engaged process, or are you just ceding leadership responsibilities? If you want to be more proactive, try discussing the vision or goals with your boss, your partner, or your community leader. Decide if you agree with that vision, and if not, ask questions and maybe pose some thoughts or creative solutions of your own. It does take time and energy, but the feeling of empowerment and active participation in the leadership process will positively impact other areas of your life. What claiming and granting behaviors have you enacted recently? I recently experienced a “gold nugget” moment in education; that is, one of those moments where a single question or piece of information can change the course of a discussion and lead to important learning.

My college was hosting a small group of business club students from a local high school. There was a scheduling snafu, and the students’ scheduled team-building activity was canceled. I happened to be in the office and had an unscheduled hour, so I hurriedly pulled together some supplies and formulated a plan. I asked the students to draw a picture of “what leadership means to me” on a small dry erase board. Being students after my own heart (and artistic ability), most of them drew stick figures. More specifically, most of them drew some version of a big stick figure telling little stick figures what to do or, for the more enlightened students, a big stick figure working alongside the little stick figures. We discussed the implications of these pictures for a few minutes, and then I asked this question: “Yesterday, how many of you participated in the student walk out about gun violence?” About ⅓ of the students raised their hands. I asked a few students to tell us about what happened, and they recounted a short time of remembrance couple with respectful activism. I then asked this question: “And who was the big stick figure who organized all of this activity?” Silence. Finally, one student spoke up, “There wasn’t a single person. Instead, it was multiple students sharing ideas and organizing. No teachers or staff were even involved.” We then talked about how, in this particular instance, leadership was clearly present and effective, but spread among many people as they shared responsibility and influence. Sure, there are times when a big stick figure is important and effective, but not always. Thus, by finding a clear recent example of shared leadership, the students were able to broaden their perspective about the very nature of leadership. In this case, one salient counterexample to their previous understanding of leadership helped to drive learning. This incident caused me to ponder: what are my own deeply held beliefs about leadership, and can I think of a clear counterexample to them? What about you? Written by Rachel Clapp-Smith Have you ever wondered if the leader you see in yourself is the leader others see? There are a host of theories I could regale you with to explain how and why we come to see ourselves as certain types of leaders. However, on the very basic level, the question of finding congruence in how we see ourselves and how others see us is a matter of self-awareness. The most important piece about becoming self-aware is getting feedback. Many organizations implement systems such as 360 assessments and annual reviews as mechanisms to provide feedback. Sounds like a good idea, right?

Well, the problem is that organizations do a good job with building the structures, but a terrible job at the very human element of the feedback loop – how to craft feedback in a developmental way, how to absorb feedback that may not always be positive, and how to turn such feedback into actionable items for improvement. If you are human like me, your gut reaction to feedback might be dread in anticipation of feedback and sulking if it is negative. Because we all feel this way, we have a tendency to give positive feedback, which is nice to have something reaffirm how great we are, but not always developmental, because it may make us think that everything we do is just fine. The truth is, we all have room for improvement. I might suggest at this point that we all just suck it up and learn how to process feedback so that we can turn it into something positive. This isn’t bad advice and I would recommend training yourself to use a learner mindset in receiving feedback about how you lead. But this blog post is about how to get really honest and complete feedback. When you want to hear the hard news, who do you turn to? The people who know you well, who support you, and who can be honest with you. In short, where strong relationships exist, so, too, does honest feedback. Because of this, it is almost silly to use only 360 degree feedback, i.e., only in the workplace. With 1080 degree feedback, that workplace information can be augmented by family and friends, and members of our community domain (volunteer organization, church group, sports club, etc.). This gives leaders a panoramic view in high definition. When the leader they see is not the leader others see, the 1080 view will make it clear why, because the feedback is more complete and in some areas, likely more honest. How often do you ask your friends and family about how they see you lead? We have evidence from our research that the way they see you lead has an awful lot to do with the way you see yourself lead. Furthermore, our research shows that the more your friends and family acknowledge you as a leader, the more effectively you lead at work. There’s a lot of power in 1080 feedback. Are you ready for it? Written by Michelle Hammond Photo by Ricardo Gomez Angel Last minute deadlines. Public speaking. Big events to plan. Traffic. Job interviews. Computer viruses. Audits. Micromanaging bosses. Buying a new car. Moving houses. Conflict with co-workers. Budget cuts. Jammed photocopiers. Are you feeling a bit stressed reading through this list? Yeah, me too! Stop for a moment and consider the nature of stress. When you think about stress, what are your thoughts? Is stress something that is always bad? Something to be avoided? Or can there be benefits or opportunities for growth?

Stress comes with a host of negative consequences, no doubt about it: headache, heart disease, reduced immune system, digestive problems, anxiety, depression, relationship strain, and the list goes on. But have there also been times in which our stress response can lead us to perform better, to overcome challenges, to connect with other people, and to grow. In research, we distinguish three related concepts: stressor, stress, and strain. Stressors are demands from the environment (i.e. the list above), stress is our momentary response to those demands when we think they tax us or exceed our abilities, and strain is the effect it takes on us over time. Stressors generally lead to stress which generally leads to strain. BUT it’s not inevitable. And that’s the key here. Stress researchers have recently discovered that how we think about the nature of stress affects how we respond to it and the long-term effect it has on us (strain). We can think about stress as something always bad that leads to bad outcomes (stress-is-debilitating mindset) or it can bring about positives as well (stress-is-enhancing mindset). Research shows that more positive views of stress (stress-is-enhancing mindset) relate to more positive physiological and behavioral outcomes such as openness to feedback, cognitive flexibility, and life satisfaction (Crum et al., 2013; Crum, et al., 2017). Stress mindset has significant effects on both physiological outcomes such as cortisol reactivity and behavioral outcomes such as the desire for feedback under stress (Crum, Salovey, & Achor. 2011; Crum et al. 2013). People holding a stress-is-enhancing mindset experienced greater increases in levels of anabolic hormones, which are associated with growth, and experience increases in positive affect and greater cognitive flexibility compared to those with a stress-is-debilitating mindset (Crum, et al., 2017). Here are two excellent videos by the leading health psychologists and researchers summarizing this research:

In my own research, we found that holding a stress-is-enhancing mindset was beneficial for job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Specifically, the negative relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction was significantly less pronounced for people who believed stress could have benefits. And they were also better able to see the benefits of participation in both roles, work-family enrichment. So it helped reduce the negative effects of the bad things and augmented the good! Win-win! The good news is that this isn’t something that you’re born with. You can change your mindset towards stress. This past year has objectively been a stressful one for me: I started a new job, managed the logistics of an international move, managed my three kids’ emotional needs through the transition, and supported my husband in his job search. And let’s not forget the smaller ways too – weaning my kid of a pacifier, trying to make new friends in a new city, and deal with the daily hassles of life. I admit there have been so many moments where I made stress my enemy and let it all get the better of me. These have been dark and ugly moments. But I’m trying to “get better at stress” by putting this research into practice. My health, my family, my students, and my colleagues, and my friends all depend on it. These are my top 3 take-away points from this research: 1. Realizing that some stress is inevitable, so not to be so shocked by it. I’m still working to reduce it in as much as possible (especially chronic stress and shadow work). When I’m feeling stressed in the moment, I try to acknowledge it to myself. I’m really feeling stressed about something right now and that shows that I care about it. It’s important to me. And that's a good thing! 2. Reframing the physiological sensations of stress as ways my body is preparing to work through what it’s facing. For me, it’s in the heart, stomach, and head. When my heart beats fast and I feel that weird feeling pit in my stomach, I try to remember my body needs energy and it’s giving it to me. A regular commitment to exercise and giving birth three times has also helped this. I’m less afraid of a little physical discomfort and I realize it will dissipate. I trust my body a bit more. 3. Trying to “tend and befriend.” When I’m feeling stressed, I try to think of how I can connect with other people. An easy go-to here is to try to physically connect with my husband or kids. A back rub or snuggle takes the focus of me and my “hot mess.” And as Kelly McGonigal states “your stress response has a built-in mechanism for stress resilience, and that mechanism is human connection.” I find this research really empowering. I’ll never win the stress game through elimination. I will work to reduce unnecessary stress and pay attention to when changes are needed. But there will always be stressors I have to face. I can't eliminate stress, but I can “get better at stress.” Stress doesn’t have to mean heart disease and reduced relationship quality. Interested in learning more? Check out the Stanford Mind and Body Lab for the research evidence, media attention and to sign up for a course on Rethinking Stress. |

|

Copyright © 2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed